Abstract:

On 14 April 1912, RMS Titanic, one of the most well-known ships in that era and hitherto, struck an iceberg while cruising at full speed towards New York City. Failing to withstand the damage, the Titanic soon sank after midnight, killing more than 1,500 people on board. This report will introduce the general information about this accident and discuss some ethical issues behind it. It is intended for the general public who is interested in the incident but has no knowledge of shipbuilding, so only the management aspects of the failure will be included.

The main reason for such a large number of deaths was the lack of lifeboats equipped. The operating company decided to carry at only a third of the design capacity which could not hold everyone on board simultaneously. The law at that time was already outdated and did not require the company to do so. The crew was also overconfident in their expertise and the engineering of the “unsinkable” ship, underestimating the risk of icebergs. The telegraphers on the Titanic did not bring all the iceberg reports they had received to the captain, and the captain ordered the ship to operate at a dangerously high speed despite the warnings. Recommendations include law revisions by the Board of Trade of the UK, requiring ships to carry sufficient lifeboats for everyone and conduct mandatory safety training. Most changes were implemented a few years after the accident, an important step towards modern sailing safety.

Background:

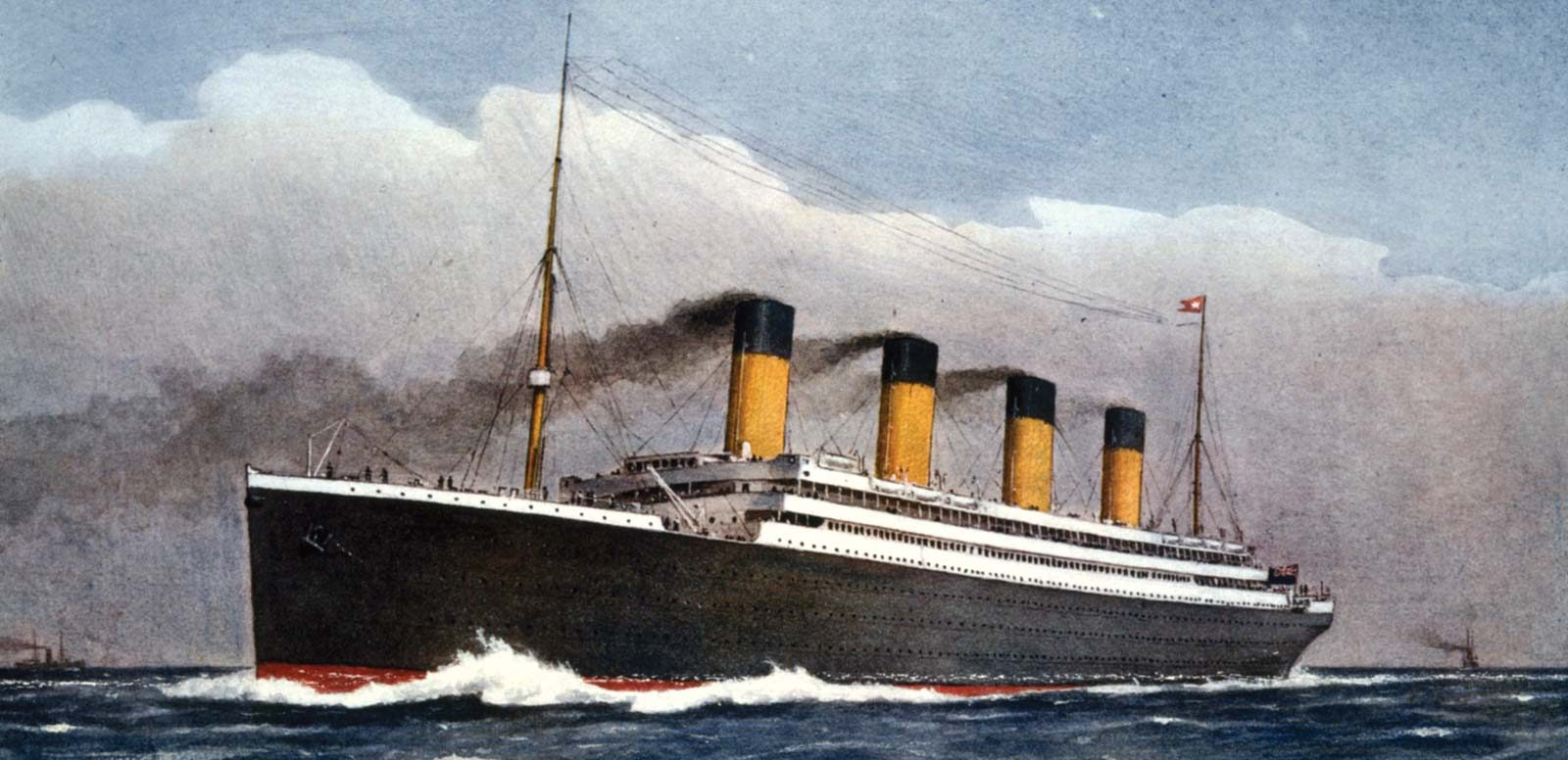

RMS Titanic, a British passenger liner operated by the White Star Line, was the largest ship in the world at its time of operation (Butler 1998). It was built by Harland and Wolf and designed by chief naval architect Thomas Andrews. Well-known for its luxury, it was equipped with facilities including gyms, swimming pools, ballrooms, and restaurants for maximum enjoyment. It was also considered an engineering miracle because it utilized the latest technologies available such as large electricity generators driven by steam and a centralized water and heating system. Safety was frequently emphasized in its advertisement, as Titanic was claimed to be “unsinkable” by the operating company.

It had its maiden voyage on 10 April 1912, traveling from Southampton to New York City. Some of the passengers were the richest and most influential people at that time who boarded for business or family trips, but most of them were impoverished immigrants from England, Ireland, and other parts of Europe seeking a new life in North America. An estimated total of 2,208 passengers was on board (ET 2021), excluding the crew.

At 11:40 PM on 14 April, a lookout on duty spotted an iceberg ahead of the Titanic, and the First Officer ordered the ship to be steered around the obstacle and the engines to be reversed, but the ship still struck the iceberg due to inertia. At least five of the watertight compartments were breached, but the ship was only designed to survive a failure of four compartments. It then sank gradually and slipped beneath the surface of the Atlantic Ocean at 2:20 AM the next day. More than 1500 people who were unable to get on the lifeboats lost their lives, the deadliest accident of a cruise ship in peacetime to date (ST 2014).

The Engineering Failure:

The main reason for such a large number of deaths was the lack of lifeboats equipped. The Titanic had 16 lifeboat frames, each capable of hanging and processing 4 lifeboats, which meant it could carry up to 64 lifeboats by design (Chirnside 2004). Those 64 lifeboats were able to fit 4,000 people at full capacity – more than the total number of people on board. The Board of Trade of the UK at that time only required ships over 10,000 tons to carry a minimum of 16 lifeboats (Hutchings and De 2016). The White Star Line decided to take 20 lifeboats capable of carrying 1,178 people, only a third of the designed limit but still exceeding the legal requirement. One important consideration behind the decision was that it believed more lifeboats were useless for a ship that were “unsinkable” because, in the event of a non-urgent accident, they would be only used for round-trip transportation to the rescue ship instead of carrying everyone at once. The company also worried about the prestige of the “unsinkable” ship, because the passengers might be frightened by the lifeboats overwhelming the deck. However, since the Titanic was not unsinkable in reality and it took a long time for nearby ships to come to the rescue, all people on board could only survive if there were sufficient lifeboats capable of carrying everyone at the same time: people who were immersed in the freezing water typically died of cardiac arrest or other bodily reactions within 15-30 minutes (Aldridge 2008). In addition, none of the crew on board were trained for shipwrecks, leaving many lifeboats underfilled at the early stage of evacuation and leading to many unnecessary deaths.

Another factor of the accident was the overconfidence of the crew who underestimated the risk of icebergs and their consequential damages. Starting from the morning of the accident, the telegraphers on Titanic had received at least five iceberg reports from different ships nearby. Only two of the reports were confirmed to be conveyed to the captain and the vice officers, while the remaining three were discarded by the telegraphers. The telegrapher on a nearby ship even claimed that he was scolded by the Titanic for flooding them with repetitive warnings. Despite the reports, the captain still ordered the ship to cruise at full speed. Many sailors like him believed that catastrophic damages to such an advanced and gigantic ship were impossible, as he declared in 1907 that he “could not imagine any condition which would cause a ship to founder, and modern shipbuilding [had] gone beyond that” (Barczewski 2006), even though these beliefs had no foundation at all. Another reason for his decision was that the Titanic might not arrive at the destination on time if it cruised at lower speeds, given that it had already detoured earlier due to weather conditions, a consequence that could possibly damage the reputation of the brand new ship and the operating company. If the ship cruised at a lower speed, the damage by the iceberg would have been within the design limit, if not avoided at all.

Ethical Analysis:

The Greek philosopher Aristotle regarded virtue as finding the “golden mean” – the middle ground between two extremes. One’s characteristic or trait should be neither in excess nor in deficiency, and a truly virtuous person should be able to choose the point which leads to the optimal outcome. One important virtue widely recognized in society is communication, which is essential for sailors on the same ship because they have different roles and are located at various locations across the ship while contributing to a common goal of ensuring safe operation. Virtue ethics is particularly suitable for analyzing the decision by the telegraphers to ignore iceberg reports since a sailor who demonstrates the virtue of communication in daily work is expected to find a balance between too little and too much communication. The telegraphers must judge the importance of a message they receive and whether or not it should be escalated to the captain. Too much communication between the telegraphers and the captain may cause unnecessary dialogs and reduced efficiency, while too little communication may lead to failure to transfer important information regarding safety. On the Titanic, the telegraphers showed insufficient communication as they wrongly decided not to bring the extra iceberg reports to the captain’s attention, which could have made an impact on his decision to adjust the speed. If they did not make the assumption that the reports were unnecessary and decided to pass every one of them to the captain, he might have been more alert of the presence of icebergs in the vicinity and decided to slow down or stop the ship accordingly, avoiding a potential accident.

The captain’s decision to drive the ship at a dangerously high speed in order to arrive on time can be best analyzed using duty ethics. Duty ethics judge whether an action is ethical by whether or not it is in agreement with a well-established rule, law, or maxim only, rather than the consequences caused by the action. This special characteristic may cause contradictions, as we will see that applying different rules can lead to opposite outcomes. One rule that the captain abided by could be “it was an employee’s responsibility to finish his job on time and protect the reputation of his company”. He had the responsibility as the captain to bring his ship to the destination according to the schedule and avoid damages to the image of his company, and his decision was justified by strictly following the rule. The issue is that though this rule sounds nothing wrong at first glance, it cannot be applied to all cases. It fails the universality principle which states that one should only act in a way that can be made into universal rules for everyone else. A company may have unreasonable rules or requirements, intentionally or unintentionally, that have the potential to endanger the well-being of its employees, customers, or society in general. Thus, blindly obeying them may sometimes lead to unethical outcomes. The rule also fails the reciprocity principle which states that one should not use others as a means. Thus, an employee should never utilize the well-being of other people in order to accomplish his or her career goals. A better maxim to consider can be “it is a captain’s responsibility to ensure the safety of his passengers”, which satisfies both the universality and reciprocity principle as it respects the right to life of the passengers and makes the society more peaceful if applied to all cases. Then, the captain’s action to operate at a high speed was not justified by the rule because the ship was more likely to hit an iceberg, endangering thousands of lives on board. Indeed, duty ethics is complicated to apply since one must consider several competing maxims and choose the one that best fits the scenario. In our case, the captain apparently chose to prioritize the rule of his company over the rule to ensure safety, which eventually led to the fatal accident.

The operating company’s decision to carry insufficient lifeboats can be analyzed with both duty ethics and utilitarianism, and we will contrast different conclusions that can be drawn by inspecting the action itself or its consequences. By law at that time, the White Star Line was only required to carry 16 lifeboats. The company decided to carry 20 lifeboats during this voyage, not only satisfying the requirement but also exceeding it by a considerable amount. Thus, assuming that the maxim we were referring to was the law itself, the decision was fully justified from the point of deontology because it abided by the maxim. However, from the point of utilitarianism which focused more on the result, the decision was less ethical because the outcome failed to maximize the happiness of everyone. In our case, we could define whether or not someone was happy as survival or death. Since no ships nearby could arrive before the Titanic fully immersed in water, to maximize the happiness of everyone on board, all people must get on the lifeboats simultaneously and wait for the rescuers. Unfortunately, the number of lifeboats available on the ship was far from enough to fit all people, which basically meant that many people on board were doomed to death since there would not be any spots left for them. As a result, only a certain group of people who were fortunate enough to get on a lifeboat survived and enjoyed their happiness, while the rest lost their lives and never had the opportunity to have their happiness. If the company instead decided to carry lifeboats at full design capacity, those people who were killed could have had the chance to get on a lifeboat and survive. Therefore, more people on board could enjoy happiness, not to mention their friends and family members who would no longer have to feel sorrowful for the loss.

One interesting factor that contributed to the wrong decisions of the crew and the company was that they both have overconfidence in the engineering of the Titanic. As previously mentioned, the captain chose to operate at a high speed, and the company decided to carry fewer lifeboats than they could and skip crew training for emergencies, simply because they believed that the ship was “unsinkable”. Ironically, there was absolutely no evidence that those claims had ever been verified using scientific methods. For example, the engineers never did a collision test or simulation to prove the robustness of the ship. It might be too hypercritical to blame them for not performing those tests because they were either unreasonably expensive or impractical given the technology in that era; however, according to duty ethics, it is still surprising that those highly experienced and educated people could act based on an absurd maxim like “it was acceptable to make important engineering decisions based on a completely unfounded assumption”. It certainly fails the universality principle: if all engineers work in this irresponsible way, then almost every product on the market will become unreliable and can malfunction at any time, which is not true in reality. Instead, the maxim that is more widely accepted among engineers is “one should only make decisions based on verified results”. Another mistake made by the company was to advertise their ship as “unsinkable” to the public. By duty ethics, the maxim they abided by was “it was acceptable for merchants to claim something though they had no proof or verification”. Such a rule violates the reciprocity principle as it infringes customers’ right to know and the right to make decisions. A lot of people at that time had a strong trust in the promotion, and though it could be difficult to estimate the actual number, one might not rule out the possibility that someone would purchase a ticket and board the Titanic solely because he or she was convinced by its safety. If the claim did not exist, he or she would not have been on board, thus avoiding the accident. All passengers deserved to know the actual safety level of the ship and decide whether or not to purchase the ticket based on truth. However, the White Star Line disclosed misleading information and interfered with people’s independent decision-making, which was unethical.

Recommendations:

The Board of Trade of the UK at that time should have updated their regulations regarding the number of lifeboats equipped on commercial ships as larger ships were introduced in the industry. Instead of setting a minimum requirement for all ships exceeding a certain tonnage, it should have had a dynamic standard based on the number of people on board. Specifically, it should have required any ship to carry sufficient lifeboats for all passengers and crews on board, with a reasonable redundancy such as 10% for backup purposes. If such a requirement existed prior to the voyage, which was not unreasonable as there already existed massive ships years before the Titanic, it would have carried at least 40 lifeboats – double of the 20 lifeboats carried in reality – capable of holding about 2500 people and more than sufficient to hold everyone on the ship. Note that the simple change would require a minimum amount of extra costs and modifications to the ship since the Titanic was already designed to carry at most 64 lifeboats, and 40 was still far from the limit. Such a change would lead to a much more ethical result, from the utilitarian view, as it would enable more people on board to survive and maximize their happiness (and probably their friends’ and families’).

Besides, the Board of Trade should have enforced safety training for crews working at a cruise line company. Companies that failed to provide such training programs should have been fined and had their license revoked. Firms should have been responsible for ensuring only employees who had received and passed the training could be on duty. Specifically, all officers should have been given less discretion in adjusting cruising speed and required to lower the speed to a specific threshold in icy conditions. They should have also participated in emergency evacuation drills conducted frequently and been educated to fill up a lifeboat before it was released. Such changes would be more ethical according to duty ethics because they abided by a rule that people always said, “one should prepare for the worst”. If everyone took precautions for the unknown even if it had a small chance of happening, society as a whole would be less vulnerable to accidents and disasters. Even if they did happen, the impact would be minimized because people had experience dealing with them. Though the ship was believed to be safe, neither the company nor the crew should have neglected the fact that shipwrecks could still happen at any time, and they must be alerted and prepared.

Additional recommendations include the introduction of laws by publishing and radio regulators to restrict misleading advertisements. The use of extreme words such as “unsinkable” should have been prohibited because they could hardly be backed by any evidence, and companies that violated the law should have been punished. Channels and newspapers should have been careful of the advertisements broadcasted and borne joint liability. These would be more ethical decisions as they followed the rule that “merchants should not advertise something that had not been proved or verified”, which could be applied universally. If all firms chose to disclose only verified information in their promotion, the consumers would be able to make rational decisions based on facts and their interests would be better protected.

Conclusion:

Looking back, the Titanic incident was both complicated and coincidental, because it was due to a series of wrong decisions by different stakeholders. Each stakeholder had the opportunity to correct the problem at some point, which could have helped prevent the tragedy entirely. If the regulators of the UK adapted their lifeboat laws more quickly to the introduction of large-tonnage ships, the White Star Line would have had no choice but to equip more lifeboats on the Titanic. If the White Star Line decided to carry more lifeboats despite the outdated law and train their crews, more lives on the Titanic could have been saved even if the ship sank unavoidably. And, if the telegraphers communicated more effectively and the captain chose safety over reputation, the Titanic might have been still intact.

The world was shocked by the incident, and many changes have been swiftly implemented afterward. Even before the accident was investigated, the White Star Line immediately recalled its ships in operation and loaded them with plenty of lifeboats that could fit all people on board. Recommendations were made by both the British and American Boards of Inquiry, stating that ships should carry sufficient lifeboats for everyone on board, and mandatory lifeboat drills should be conducted. Two years after the sinking of the Titanic, the new International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea was passed (SOLAS 1914) incorporating these recommendations. However, people should still be aware that laws are always limited since they can be obsolete, incomplete, or vague. In many cases, they can only instruct us on what should not be done, but not what should be done. From the Titanic, we have learned that the presence of regulations is indispensable, but it is equally important for an entity to act responsibly even if there is no legal obligation to do so, a result of proper rules, education, and social environment.